Emotional Safeness Therapy (EST) is a new integrative treatment for recurrent depression and co-occurring personality problems. The EST has been successfully implemented and run as group therapy over three years (2015-2018) at an outpatient unit of the Akershus University Hospital in Norway.

You can read more about the work on the development and implementation of Emotional Safeness Therapy in my article: EST Project – Development of Multidimensional Model of Change and Emotional Safeness Therapy.

Theoretical underpinnings of EST

Emotional Safeness Therapy should not be viewed as a novel approach since it is not rooted in own, distinct scientific tradition. On the contrary, the foundations of the treatment are based solely on preexisting and well-established conceptual and empirical work conducted within multiple scientific paradigms.

The uniqueness and distinctiveness of the EST lies in its innovative re-configuration and integration of the established treatment strategies.

The theoretical underpinnings of Emotional Safeness Therapy are rooted in two distinct scientific traditions: (1) contextual behavioral science on the one hand and (2) evolutionary psychology and social neuroscience on the other.

At the technical level, Emotional Safeness Therapy integrates various clinical strategies, partly originally developed and partly borrowed, among others, from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Compassion Focused Therapy.

Who’s the public enemy no 1?

Epidemiological studies show that the most common mental disorder, depression, is also a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Unfortunately, depression gains more and more of its destructive power each year, according to the research.

Depression is not just a “bad mood disorder”. It is a complex psychological and biological condition. Never underestimate the seriousness of depression! It is, among others, associated with a shorter life span and increased risk of major medical disorders. When depression co-occurs with a medical illness, it increases treatment costs by 150 percent. Depressed patients show also lower treatment compliance and have a shorter life expectancy (Kupfer et al., 2003).

Furthermore, depression is strongly linked to an increased suicide risk. Research shows that about 2/3 of people who complete suicide are depressed at the time surrounding their death (American Association of Suicidology). It means that up to 600 000 depressed people across the world choose to take their own lives each year. These sad numbers are continuously growing.

According to the World Health Organization, by 2020 depression will produce the second largest disease burden worldwide. And by 2030 the amount of disability and life loss due to depression will be greater than that of any other condition, including accidents, homicides, wars, cancer, heart diseases and stroke.

Oh yeah, there is a much higher risk that our lives will be prematurely terminated by depression than by war, accident, natural disaster or terrorist attack. Yet, mass-media pay relatively little attention to this danger as compared to others, more spectacular ones. Front-line fighters in the continuous battle against this threat are mental health professionals. If you you’re reading this article, you are probably one of them.

Unfortunately, the data from epidemiological studies suggest that something is fundamentally wrong and erroneous with our mainstream approach to depression. So, let’s take a closer look at the field!

What can we learn from epidemiological studies?

Except a clear message that we’re losing the battle against the epidemic of depression, the two most important take-home messages from the studies are: (1) depression has a very high rate of recurrence, and (2) depression has a very high rate of comorbidity (co-occurrence) with personality problems.

Both messages should influence the way we treat depression. But do they?

Marathon or sprint?

Research shows that at least 50% of those who recover from a first episode of depression will have a new episode within the next five years. After the second episode the risk of having recurrent episodes increases to at least 80%. On average, individuals with a history of depression will have five to nine separate depressive episodes in their lifetime.

What does it mean? It means that, in practice, depression is a recurrent condition and should be treated as such.

Thus, clinical trials based on pre- to post-treatment reduction of symptoms have little sense, beyond securing publicity for their authors. What we really need to know is how the particular treatment works in the long run, let’s say five years.

From an epidemiological point of view the ability to prevent a new episode is a much better criterion of valuing an approach than a rapid symptom reduction during the current episode. And the both features of a treatment do not need to be associated. Would you evaluate marathon runners on the basis of how well they perform during the first mile? It could be misleading, couldn’t it? Yet, we do this while evaluating and choosing treatment strategies for depression.

Is depression a single picture or just a piece of a puzzle?

The second take-home message from epidemiological studies says that when treating depressed patients, we have to be prepared to deal with personality problems. An impressively large meta-analysis of 122 epidemiological studies conducted in the course of three decades and containing data from 25 000 participants (wow!) has shown a high prevalence of personality disorders in patients suffering from mood disorders.

About 45 percent of depressed patients meet also diagnostic criteria of at least one personality disorder. In dysthymia this rate increases to 66 percent, that is to 2/3 of the sample (!!!) These numbers would become even higher if we took into account the subclinical level of personality problems.

What does the data tell clinicians? Well, the co-occurrence does not automatically imply causation. But the diagnosis of any personality disorder requires its early onset, pervasiveness, stability over time and long duration. So, personality disorders are widely considered by clinicians as vulnerability factors for “symptom disorders”, like depression, and not vice versa.

In fact, there is a large body of research on personality traits associated with depression. A review of such studies would exceed the scope of this article, but what they clearly show is that the most prevalent personality disorders that co-occur with depression belong to cluster C: avoidant, dependent and obsessive-compulsive. They all share a high level of social anxiety, emotional inhibition and coercive self-control.

In plain language: people with cluster C personality disorders tend to not be especially kind towards themselves and are at an increased risk of falling emotional victims to their social environment. Those traits can be worked on during psychotherapy.

Intra- vs interpersonal focus in therapy

All kinds of personality problems, from subclinical to severe, mean always some degree of interpersonal impairment. Interpersonal difficulties are broadly viewed by clinicians as the defining feature of personality disorders. In fact, the current DSM-classification mentions two areas of personality functioning that can be affected in personality disorders: (1) sense of self and (2) interpersonal functioning. Both areas are interrelated.

So, considering the very high prevalence of personality problems in depressed patients, don’t you think that an effective (in the long run) treatment for depression should explicitly focus on these two areas? Do you believe that challenging (or defusing from) pessimistic thoughts, or exercising, or regulating serotonin level will lead to long-lasting outcomes? Can we treat submissiveness or emotional dependency this way?

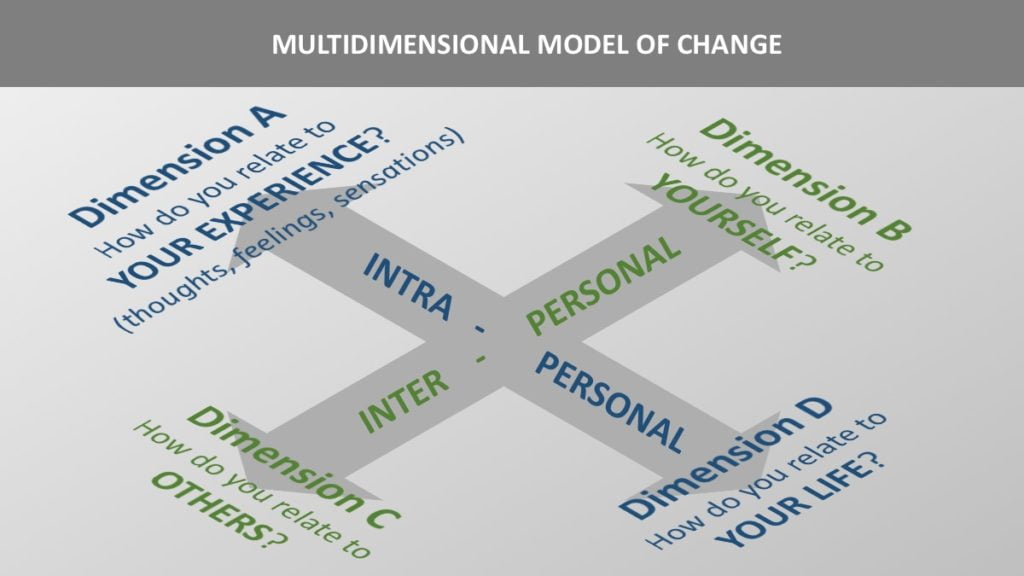

And here the Multidimensional Model of Change comes into play. Both domains (relation to self and to others) are explicitly included in the Model (Dimensions B and C) and form its Interpersonal axis (axis 2).

Multidimensional Model of Change

As I wrote in my last article, the distinction between interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions of psychological functioning has been present in literature for decades. Of course, the demarcation line is subtle, and the dimensions partially overlap, but so is the case with all distinctions in psychology.

The construction of the Multidimensional Model of Change is based on this distinction and it further subdivides the two traditional dimensions into four subdimensions: (A) relation to own experience, (B) relation to self, (C) relation to others and (D) relation to own conceptualized life. The four subdimensions still form two axes: (1) Intrapersonal and (2) Interpersonal, however their subdivision gives clinicians a more precise conceptual tool. Graphically the model looks like this:

The Multidimensional Model of Change has been created to help clinicians keep a balanced focus on different areas of psychological functioning during therapy.

For example, a client may report difficult feelings (like fear of being rejected, or shame of having been cheated on) as emotional obstacles for having a fulfilling life. A therapist then may excessively focus on the client’s personal values/goals and on the regulation or acceptance of difficult feelings in order to help her pursue the chosen life directions. This would be a typical work on the intrapersonal axis and it may quickly produce results due to activating the client to initiate new social interactions. But this work may be done at the expense of ignoring the client’s distorted sense of self and dysfunctional interpersonal attitudes (interpersonal axis). Such approach may be counterproductive in a longer perspective, leading to a new, inevitable emotional “catastrophe” in the future.

Many depressed clients would choose “having friends” or “being in love” as their values. But pursuing these values in a submissive or dependent way would only make things worse for them in the long run. So, while the traditional ACT therapist focuses on which direction the client moves (towards values or away from them), the EST therapist focuses also on the style of the client’s movements.

Generally speaking, the MMC provides clinicians with guidance for delivering more balanced interventions.

You can find a more detailed description of the Multidimensional Model of Change in my previous article.

Emotional Safeness Therapy – an overview

Emotional Safeness Therapy unifies therapeutic strategies aimed at rapid symptom reduction with strategies targeting relatively stable personality traits and those interpersonal styles that account for long-term vulnerability for depression. The aim of the intervention is to treat current depression, prevent future relapse and enhance overall quality of life.

While the Multidimensional Model of Change in itself is like an empty, a-theoretical vessel and it does not imply the use of any particular treatment, Emotional Safeness Therapy fills it with specific concepts, therapeutic goals and strategies of change.

So, what can the client expect from this therapy?

The therapy sets up two overarching goals that are pursued simultaneously during the treatment:

(1) Enhancing the client’s psychological flexibility on the intrapersonal axis, and

(2) Enhancing the client’s emotional safeness on the interpersonal axis.

Emotional Safeness Therapy views (1) psychological flexibility and (2) emotional safeness as two psychological pillars of mental health. Each of them may play more or less important role in different types of mental health problems. However, taking into account that the diagnostic category of depression (and dysthymia) refers to a heterogenous cluster of problems, the therapist should be prepared to work on both goals simultaneously.

The strategies of pursing the two therapeutic goals are borrowed respectively from (1) Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and (2) Compassion-Focused Therapy / evolutionary psychology.

More specific goals for the four subdimensions are:

- Dimension (A) – AWARENESS in relation to own experience

- Dimension (B) – SAFENESS in relation to self

- Dimension (C) – CONNECTEDNESS in relation to others

- Dimension (D) – EMPOWERMENT in relation to own life

So, graphically the EST treatment model looks like this:

What are psychological flexibility and emotional safeness?

Psychological Flexibility is a central concept in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. It is defined as “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves valued ends”. The concept is well-described in the ACT-related literature, so you can consult sources.

Emotional Safeness (as distinct from emotional safety) is a new term, but it refers to well-elaborated and established concepts. It may be defined as a sense of acceptance, support, warmth, soothing and reassurance in the relationship with oneself. The sense of emotional safeness is fostered by self-nurturance, self-care, self-reassurance and self-compassion. It is thought to be undermined by self-coercion and self-criticism.

The term “emotional safeness” is derived directly from the term “social safeness” proposed by Paul Gilbert as a part of his tripartite model of affect regulation.

The distinction between “safety” and “safeness” is central here. It has been first made by an ethologist, Michael Chance, to distinguish two motivational processes. While (1) safety focuses on becoming safe from threats (stopping and preventing bad things from happening), (2) safeness focuses on confidence and freedom to try new things.

Safety-based motivation is defensive and behavior-narrowing by its nature. Safeness-based motivation has joyful and explorative qualities.

The idea of non-defensive safeness is also the core element of the attachment literature. According to Bowlby, secure attachment creates “a safe base” from which the world can be explored with freedom to take risks and make mistakes, and psychologically grow on them.

Gilbert proposed social safeness as a distinct affective experience characterized by a sense of belonging, being wanted, accepted and cared for, warmth, connectedness and reassurance in social relations. Social safeness is thought to be linked to compassion, affiliation and attachment.

Due to their ability for perspective-taking, human beings – contrary to other mammals – are able to relate not only to others but also to themselves, and to create self-to-self relationships of the same emotional qualities as other interpersonal relationships. These may be permeated by the sense of safeness on one side, and the sense of insecurity or threat on the other.

Thus, the term “emotional safeness” extends the qualities of “social safeness” to the client’s relation with oneself. Emotional Safeness Therapy views this dimension of psychological functioning as crucial for mental health. While we can’t completely control the way other people treat us, we can always change the way we treat ourselves.

Paraphrasing Bowlby, emotional safeness may be defined as “a safe emotional base in the relationship with oneself, from which the world (including interpersonal relationships) can be explored in a flexible and non-defensive way”.

The content of the intervention

Well, this topic would exceed the scope of the article. To those who already know both ACT and CFT the landscape will look very familiar. It’s like looking at well-known furniture after it has been moved to a new house. Some things still stay next to each other, while other have been rearranged and placed in different rooms. And, as always when we move, some new items are bought and same old left behind.

Curious? Stay attuned!

READINGS:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2015). DSM-5® Classification. American Psychiatric Pub.

- Bowlby, J. (2012). A secure base. Routledge.

- Burcusa, S. L., & Iacono, W. G. (2007). Risk for Recurrence in Depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(8), 959–985. doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005

- Friborg, O., Martinsen, E. W., Martinussen, M., Kaiser, S., Øvergård, K. T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2014). Comorbidity of personality disorders in mood disorders: a meta-analytic review of 122 studies from 1988 to 2010. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 1-11. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.023.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 15(3), 199-208. doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264

- Gilbert, P. (2016). Human nature and suffering. Routledge.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(1), 1-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

- Kelly, A.C., Zuroff, D.C., Leybman, M.J. et al. Cogn Ther Res (2012) 36: 815. doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9432-5

- Kerr, S., Goldfried, M., Hayes, A., Castonguay, L., & Goldsamt, L. (1992). Interpersonal and intrapersonal focus in cognitive–behavioral and psychodynamic–interpersonal therapies: A preliminary analysis of the Sheffield Project. Psychotherapy Research, 2(4), 266-276. doi.org/10.1080/10503309212331333024

- Kupfer, D. J. and Frank, E. (2003), Comorbidity in depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108: 57-60. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.12.x

- McHugh, L., & Stewart, I. (2012). The self and perspective taking: Contributions and applications from modern behavioral science. New Harbinger Publications.

- Weinberger, A., Gbedemah, M., Martinez, A., Nash, D., Galea, S., & Goodwin, R. (2018). Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: Widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1308-1315. doi:10.1017/S0033291717002781

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply